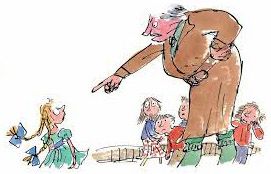

Miss Trunchbull, the Headmistress, was something else altogether. She was a gigantic holy terror, a fierce tyrannical monster who frightened the life out of pupils and teachers alike. There was an aura of menace about her even at a distance, and when she came up close you could almost feel the dangerous heat radiating from her as from a red-hot metal. When she marched - Miss Trunchbull never walked, she always marched like a storm-trooper with long strides and arms aswinging - when she marched along a corridor you could actually hear her snorting as she went, and if a group of children happened to be in her path, she ploughed through them like a tank, with small people bouncing off her to left and right. Thank goodness we don't meet many people like her in this world, although they do exist and all of us are likely to come across at least one of them in a lifetime. If you ever do, you should behave as you would if you met an enraged rhinoceros out in the bush - climb the nearest tree and stay there until it has gone away. This woman, in all her eccentricities and in her appearance, is almost impossible to describe, but I shall make some attempt to do so a little later on.

and, as promised, a little later on . . . .

Now most head teachers are chosen because they possess a number of fine qualities. They understand children and have the children's best interests at heart. They are sympathetic. They are fair and they are deeply interested in education. Miss Trunchbull possessed none of these qualities and how she got into her present job was a mystery. She was above all a most formidable female. She had once been a famous athlete, and even now the muscles were still clearly in evidence. You could see them in the bull-neck, in the big shoulders, in the thick arms, in the sinewy wrists and in the powerful legs. Looking at her, you got the feeling that this was someone who could bend iron bars and tear telephone directories in half. Her face, I'm afraid, was neither a thing of beauty or a joy for ever. She had an obstinate chin, a cruel mouth and small arrogant eyes. As for her clothes . . . they were, to say the least, extremely odd. She always had on a brown cotton smock which was pinched in around the waist with a wide leather belt. The belt was fastened in front with an enormous silver buckle. The massive thighs which emerged out of the smock were encased in a pair of extraordinary breeches, bottle-green in colour and made of coarse twill. These breeches reached to just below the knees and from there on down she sported green stockings with turn-up tops, which displayed her calf muscles to perfection. On her feet she wore flat-heeled brown brogues with leather flaps. She looked, in short, more like a rather eccentric and bloodthirsty follower of the stag-hounds than the headmistress of a nice school for children.

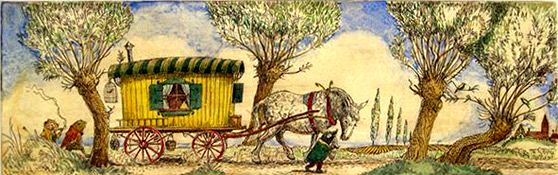

When they were quite ready the now triumphant Toad led his companions to the paddock and set them to capture the old grey horse, who, without having been consulted, and to his own extreme annoyance, had been told off by Toad for the dustiest job in this dusty expedition. He frankly preferred the paddock, and took a great deal of catching. Meantime Toad packed the lockers still tighter with necessities and hung the nosebags, nets of onions, bundles of hay and baskets from the bottom of the cart. At last the horse was caught and harnessed and they set off, all talking at once, each animal either trudging by the side of the cart or sitting on the shaft, as the humour took him. It was a golden afternoon. The smell of the dust they kicked up was rich and satisfying; out of thick orchards on either side of the road birds called and whistled to them cheerily; good-natured wayfarers, passing them, gave them "Good-day," or stopped to say nice things about their beautiful cart; and rabbits, sitting at their front doors, held up their fore-paws and said, "Oh my! Oh my! Oh my!"

Late in the evening, tired and happy and miles from home, they drew up on a remote common far from habitations, turned the horse loose to graze and ate their simple supper sitting on the grass by the side of the cart.

The fireworks were by Gandalf : they were not only brought by him, but designed and made by him; and the special effects, set pieces, and flights of rockets were let off by him. But there was also a generous distribution of squibs, crackers, backarappers, sparklers, torches, dwarf-candles, elf-fountains, goblin-barkers and thunder-claps. They were all superb. The art of Gandalf improved with age.

There were rockets like a flight of scintillating birds singing with sweet voices.

There were green trees with trunks of dark smoke : their leaves opened like a whole spring unfolding in a moment,

and their shining branches dropped glowing flowers down upon the astonished hobbits,

disappearing with a sweet scent just before they touched their upturned faces.

There were fountains of butterflies that flew glittering into the trees;

there were pillars of coloured fires that rose and turned into eagles,

or sailing ships, or a phalanx of flying swans;

there was a thunderstorm and a shower of yellow rain;

there was a forest of silver spears that sprang suddenly into the air with a yell like an embattled army,

and came down again into the Water with a hiss like a hundred hot snakes.

There was also one last surprise, in honour of Bilbo, and it startled the hobbits exceedingly, as Gandalf intended.

The lights went out. A great smoke went up.

It shaped itself like a mountain seen in the distance, and began to glow at the summit.

It spouted green and scarlet flames. Out flew a red-golden dragon - not life-size, but terribly life-like :

fire came from his jaws, his eyes glared down; there was a roar, and he whizzed three times over the heads of the crowd.

They all ducked, and many fell flat on their faces.

The dragon passed like an express train, turned a somersault, and burst over Bywater with a deafening explosion.

"That is the signal for supper!" said Bilbo.

Never in all their lives had Dick and Dorothea seen so many boats. Mrs.Barrable had taken them shopping at a store that seemed to sell everything possible for the insides and outsides of sailors. She had taken them to lunch at an inn where everybody was talking about boats at the top of his voice. Now they had gone down to the river to look for the Horning boatman and his motor-launch. The huge flags of the boat-letters were flying from their tall flag-staffs. Little flags, copies of the big ones, were fluttering at the mastheads of the hired yachts. There were boats everywhere, and boats of all kinds, from the big black wherry with her gaily painted mast, loading at the old granary by Wroxham bridge, and meant for nothing but hard work, to the punts of the boatman going to and fro, and the motor-cruisers filling up with petrol, and the hundreds of big and little sailing yachts tied to the quays, or moored in rows, two or three deep, in the dykes and artificial harbours beside the main river.

"Why are such a lot of boats wearing dust-covers ?" asked Dorothea. "Rain-coats, really" answered Mrs.Barrable. "Those are awnings. Everybody rigs them at night to make an extra room by giving a roof to the steering well, and, of course, when the boats are not in use the awnings keep them dry. Lots of the boats are not let yet. Luckily for us it's early in the season. Later on people come here from all over England, and in the summer Wroxham must be like a fairground." "It's rather like one now," said Dorothea, listening to the gramophones and the hammering in the boat-sheds. "Oh, look. There's someone just starting. Do all the big boats have little ones like chickens hanging on behind ?" "Dinghies," said Mrs.Barrable. "Suppose you're in a yacht and want to fetch the milk or post your letters, you just jump into your dinghy and use your oars." At that moment she saw the boatman waving to them, and a minute or two later they were off themselves, in a little motor-launch, purring down Wroxham Reach. In the bows of the launch were the two small suit-cases, and the parcels that had been sent down to the river by the people at the village store. Dorothea looked happily at one large, awkward, bulging parcel. Mrs.Barrable had bought them cheap oil-skins and sou'westers as well as sea-boots. There was no excuse for wearing such things on a fine spring day, with bright sunshine pouring down, but just to look at that bulging parcel made Dorothea feel she was something of a sailor already.